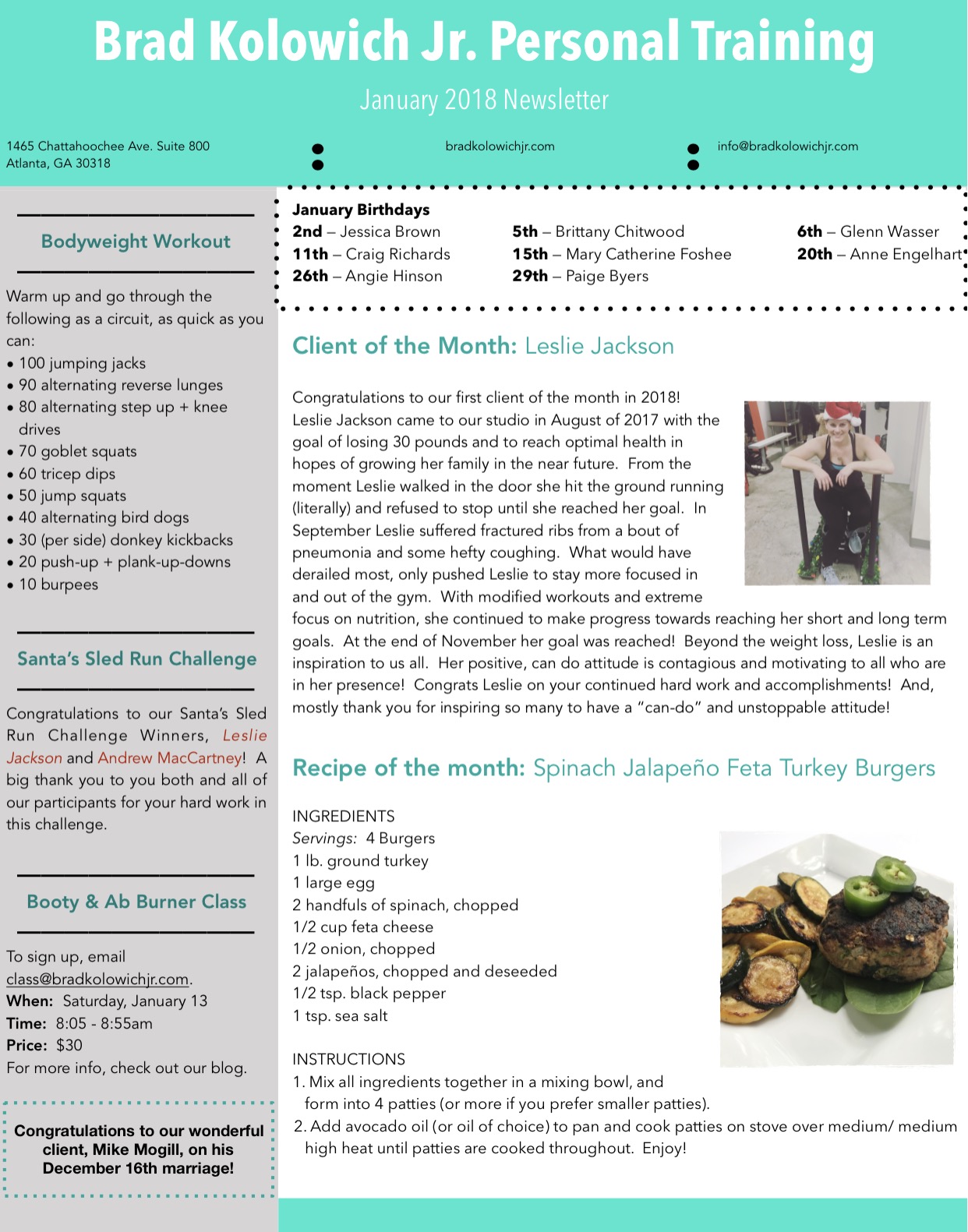

Periodically, we see reports that scientists are closer to developing a pill that would mimic the benefits of exercise. The truth is that no medication or supplement even comes close to exercise for being able to do so much for so many people — or probably ever will. Although we’ve all heard that regular exercise can improve heart health, strengthen muscles and help protect bones, it can also enhance the quality of your life in a number of ways.Here are six benefits that may surprise you.

Better sex

In men, regular exercise appears to be a natural Viagra: It’s associated with a lower risk of erectile problems. In one study, sedentary middle-aged men assigned to participate in a vigorous exercise program for nine months reported more-frequent sexual activity, improved sexual function and greater satisfaction. Those whose fitness levels increased most saw the biggest improvements in their sex lives. Research in women has found that those who are physically active report greater sexual desire, arousal and satisfaction than women who are sedentary.

Increased blood flow helps explain these findings. An enhanced self-image from exercise may play a role, too. Men and women who exercise may be more likely to feel sexually desirable, which can lead to better sex. So can the greater strength, flexibility and stamina that result from exercise.

In addition, physical activity — especially strength training — can increase levels of testosterone, which may boost sex drive in both men and women. It’s worth noting that overtraining can have the opposite effect: A recent study found that men who do very vigorous exercise on a regular basis tend to have lower libidos. Although this is a potential concern for elite athletes or others who push themselves to the max without adequate recovery, it’s not something that most of us need to worry about.

Sounder sleep

A review of 66 studies on exercise and sleep concluded that regular exercise is comparable to sleep medication or behavioral therapy in improving the ability to fall asleep, as well as sleep duration and quality.

Researchers aren’t sure why, but they suspect physical activity may help by affecting body temperature, metabolic rate, heart rate or anxiety levels, among other things, in a way that helps us fall asleep and stay asleep.

Because exercise also revs up your body, conventional wisdom has it that exercising in the evening can interfere with sleep. But overall, research has failed to support this assertion. For example, a small study of young adults found that doing vigorous aerobic exercise two hours before bedtime did not impair their ability to fall asleep or sleep soundly. Likewise, a small study of a group of older men and women showed that low-impact aerobic workouts done between 7 p.m. and 8:30 p.m. were just as effective as morning workouts at improving their self-reported sleep quality. And a larger 2013 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America poll found that while responders who exercised in the morning reported the most favorable sleep quality, those who vigorously exercised in the evening said they slept just as well, if not better, on days they exercised than on those that they did not.

Of course, everyone is different, so it’s possible that nighttime exercise may make it harder for you to sleep. But the only way to know for sure is to try. You may be pleasantly surprised at what a little pre-bedtime sweat can do for your sleep.

Fewer colds

You may have heard fitness buffs claim that they never get sick. Although this may seem like baseless — not to mention annoying — boasting, there is scientific truth to it. Numerous studies have linked regular exercise to a lower risk of colds. For example, a study that followed about 1,000 adults for three months found that those who did aerobic exercise at least five days a week were about half as likely to develop colds as those who didn’t exercise. And when exercisers did catch colds, they had fewer and less-severe symptoms than their couch-potato peers.

These studies, which show associations but not cause and effect, are corroborated by randomized trials on exercise and colds. In one such experiment involving sedentary postmenopausal women, participants were assigned to either moderately intense exercise (such as brisk walking) five days a week or once-a-week stretching. By the final three months of the 12-month study, those doing the regular exercise reported having substantially fewer colds than the stretchers.

Research in animals and humans suggests that exercise chases away colds by boosting the immune system. At the same time, very intense activities may suppress immunity by increasing levels of the stress hormones cortisol and adrenaline. That perhaps explains why, in one study, runners who participated in a Los Angeles marathon were nearly six times as likely to get sick in the week after the race as runners who did not participate.

Although this is a potential issue for elite athletes or people who do marathons or triathlons, the level of activity among most exercisers — even if it’s vigorous — is far more likely to keep colds at bay than bring them on.

Healthier eyes

When you hear about a connection between exercise and eyesight, maybe you picture those eye exercise programs that promise to sharpen your vision. But that’s not what we’re talking about. Instead of moving your eyes, the idea is to move your feet.

Research shows that people who are physically active have a lower risk of cataracts. For example, a study of nearly 50,000 runners and walkers found that those who exercised most vigorously were 42 percent less likely to develop cataracts than those who exercised least vigorously. Exercisers who fell in the middle in terms of intensity were also at reduced risk, though to a lesser degree.

The same researcher found a similar benefit regarding age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of vision loss, in a study of nearly 42,000 runners. The more that people ran, the more their risk of AMD appeared to decline. A different study, which followed roughly 4,000 people for 15 years, showed that participants who were physically active were less likely to develop AMD than those who weren’t active.

Scientists aren’t sure why exercise protects against cataracts and AMD. One possibility is that it reduces inflammation, which is associated with both conditions. Cataracts and AMD have also been linked to risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including elevated blood sugar and triglycerides, which regular exercise can improve. Further, some research suggests that people who are overweight or obese are more prone to cataracts and AMD, so physical activity may help by preventing weight gain.

Protection against hearing loss

You heard it here first: Exercise may be good for your hearing. A study of more than 68,000 female nurses who were followed for 20 years found that walking at least two hours a week was associated with a lower risk of hearing loss. Other research has linked higher cardiovascular fitness levels with better hearing.

Exercise may protect against hearing loss by improving blood flow to the cochlea, the snail-shaped structure in the inner ear that converts sound waves into nerve signals that are sent to the brain. What’s more, it may prevent the loss of neurotransmitters, which carry those signals between nerve cells. Exercise may also help by reducing the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, both of which are linked to hearing loss.

Of course, blasting music into your ears while you exercise could have the opposite effect and do damage to your hearing. Noise-canceling headphones are a good option because they reduce the need to turn up your music as much. But don’t use them while exercising in isolated spots or on a busy road, where you might not notice approaching traffic.

Better bathroom habits

Although high-impact activities such as jumping or running can cause women to leak urine, research shows that moderate exercise may decrease the risk. For example, a study of middle-aged female nurses found that those who were physically active had lower rates of urinary incontinence than women who were inactive. A study of older nurses by the same team of researchers yielded similar findings.

A urinary problem familiar to many middle-aged and older men is nocturia, the need to get up more than once a night to pee. Often the cause is an enlarged prostate, a condition known as benign prostatic hyperplasia, or BPH. Exercise can help prevent nocturia or reduce its severity. In a large study of men with BPH, for example, those who were physically active for an hour or more per week were less likely to report nocturia than those who were sedentary. Likewise, a study of sedentary older men found that after eight weeks of daily walking, they urinated less frequently during the night.

Another common bathroom-related problem for both men and women is constipation, which exercise can help improve as well. In a study of 62,000 women, those who reported daily physical activity were nearly half as likely to experience constipation as women who exercised less than once a week. A randomized trial involving inactive, middle-aged men and women with chronic constipation found that those assigned to a 12-week exercise program were able to poop more easily.

Exercise helps by decreasing what is referred to as “transit time.” That’s how long it takes food to move through the digestive tract — not, as it sounds, the amount of time it takes to get to work. Alas, a shorter commute is one benefit that exercise may not have — unless, of course, biking to work is faster for you than sitting in your car in heavy traffic.

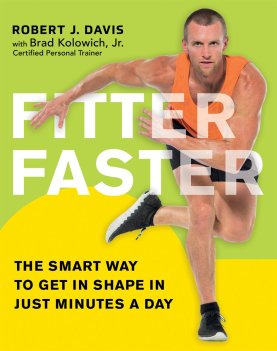

Davis has written several books about health issues. This is adapted from “Fitter Faster: The Smart Way to Get in Shape in Just Minutes a Day” by Davis with Brad Kolowich Jr.